Panini’s Grammar: Foundations of Linguistic Science

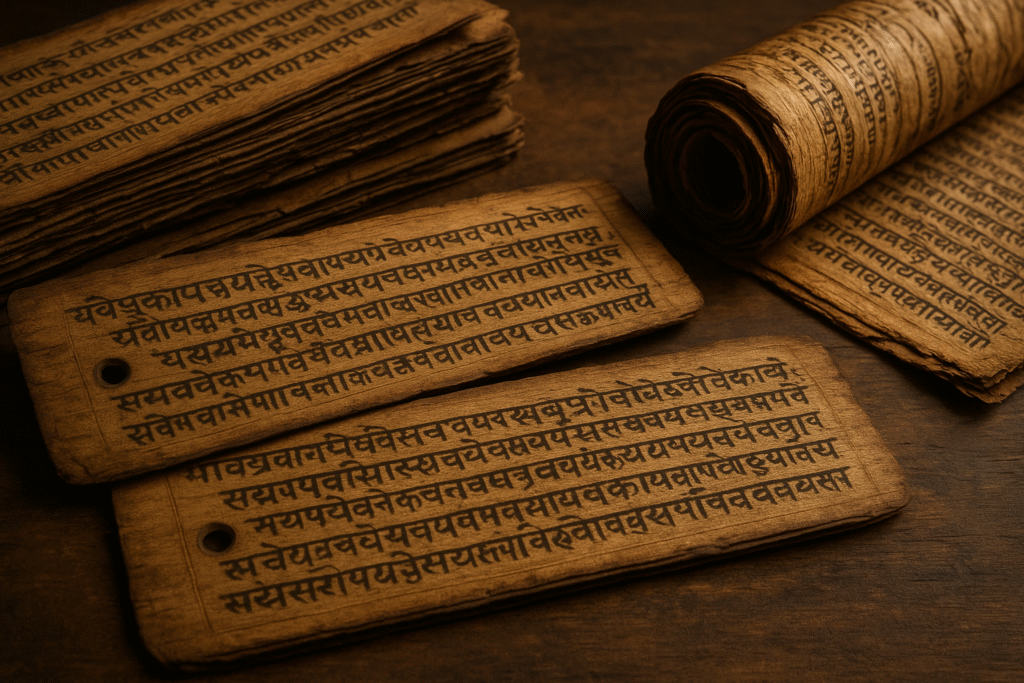

Long before the world spoke of syntax, semantics, and linguistics as formal disciplines, the ancient land of Bharat whispered the rhythms of language through sacred chants, poetic verses, and philosophical debates. Nestled amidst the dusty scrolls of antiquity lies the story of a sage named Panini—whose mind mirrored the cosmos in its structure, and whose gift to the world was not just grammar, but a profound framework for understanding the essence of communication, thought, and consciousness.

The Sound of the Sacred

In the villages of ancient India, language wasn’t merely a tool—it was an offering. Words carried weight. They were chanted to invoke the gods, to encode philosophy, to pass on traditions. Sanskrit, with its luminous syllables, was believed to be the language of the divine. And amidst this sanctified world of sound, arose a young mind who would map its every corner.

Panini was born in Shalatura (modern-day Pakistan) around the 4th century BCE. Legend says he grew up amidst the echoes of the Vedas and the vibrant debates of scholars. But instead of being overwhelmed, he listened—deeply, intuitively. What he heard wasn’t chaos, but patterns. And through years of study, reflection, and sādhanā, he transformed the living river of Sanskrit into a structured, flowing grammar—Ashtadhyayi—a composition of eight chapters, distilled like divine nectar.

Ashtadhyayi: More than a Grammar

At first glance, Panini’s Ashtadhyayi may appear as a technical manual—3,959 aphorisms, sharp and concise. But look closer, and you’ll find the pulse of a civilisation.

His work wasn’t just about nouns and verbs—it was about order, precision, sound, and meaning. He created a meta-language to describe language. He used operational rules (sutras) in a manner that mirrored algorithms and modern computing logic, centuries before such concepts existed.

The elegance of Panini’s system lies in its brevity and generativity. It could produce an infinite array of expressions from a finite set of rules—just like nature itself. Some scholars have even compared it to a programming language—predictive, coded, and intelligent.

Language as Sacred Geometry

To truly appreciate Panini’s genius, we must step into the philosophical heart of India. Here, sound (nāda) is creation. The vak (speech) of the Veda is not mere utterance—it is Shakti, the divine feminine, the energy of the cosmos. To map this sacred sound was to engage in a spiritual act.

Thus, Panini was not merely a linguist. He was a rishi, a seer. His grammar was not a book, but a mirror to the universe—revealing how creation organizes itself through patterns, rules, and resonance. In Indian classical dance and music, we still witness his legacy, where each movement or note corresponds to a deeper symbolic language encoded long ago.

Echoes in the Modern World

Today, Panini’s influence extends far beyond the Sanskrit classroom. His structural brilliance inspired modern linguists like Ferdinand de Saussure and Leonard Bloomfield. Computer scientists find in his sutras a precursor to formal language theory. In fact, Noam Chomsky’s generative grammar—considered a cornerstone of modern linguistics—bears striking parallels to Panini’s system.

Yet beyond the accolades and academic relevance, Panini’s work stands as a reminder of India’s timeless ethos—that knowledge is sacred, that intellect can be a path to the divine, and that language, when revered, becomes a bridge between the human and the eternal.

A Legacy That Speaks

In a world increasingly fragmented by miscommunication, Panini offers us a path of clarity, structure, and elegance. His legacy urges us to listen more deeply—not just to words, but to the spaces between them, to intention, to rhythm, to silence.

As we trace our fingers across the pages of Ashtadhyayi, we aren’t merely reading grammar—we are entering a dance of intellect and intuition, logic and luminosity. And in doing so, we reconnect with a heritage that sees the spoken word not just as expression—but as pranava, as breath, as sacred.

Let us speak, then, with reverence. Let us learn, not to master language—but to honour it.