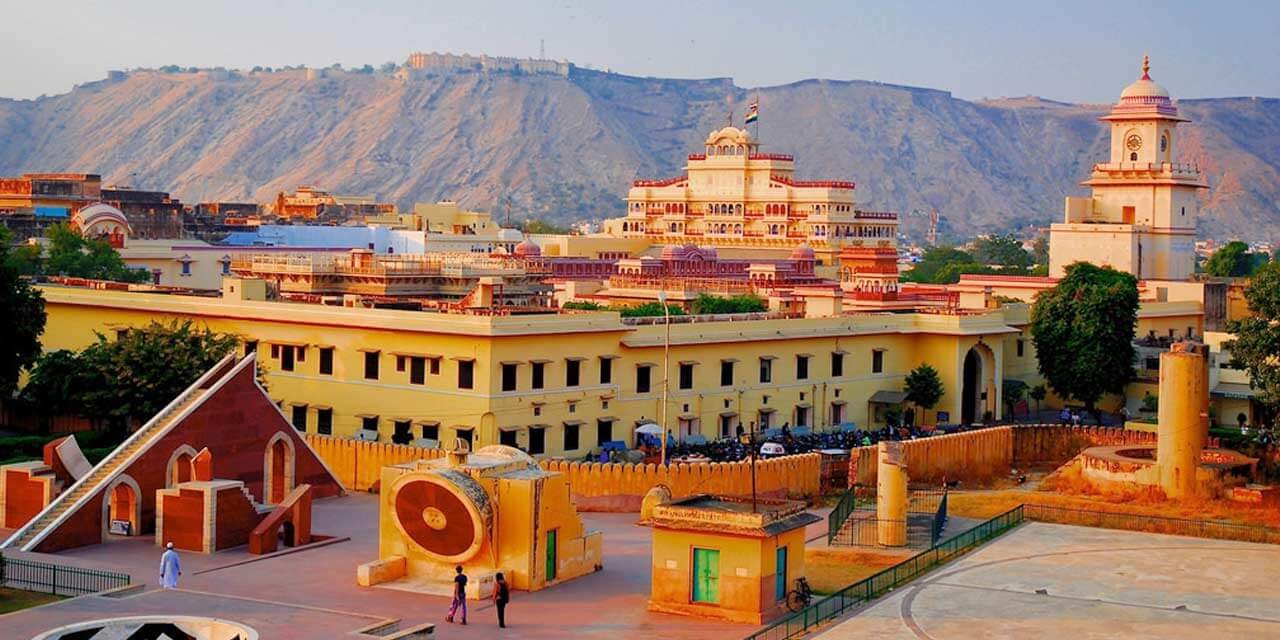

In the heart of Jaipur, amidst the bustling streets and vibrant palaces of Rajasthan’s Pink City, stands a silent sentinel of scientific brilliance—Jantar Mantar. At first glance, it may seem like a collection of oddly shaped stone sculptures or abstract installations. But look closer, and you’ll discover one of India’s most remarkable achievements in astronomy—a fusion of architecture, observation, and cosmic understanding, carved into stone.

Built in the early 18th century by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, Jantar Mantar is not merely an observatory—it is a monument to the rational mind, a tangible expression of India’s rich legacy in mathematics, astronomy, and architecture. Jai Singh, a visionary ruler and a scholar deeply influenced by ancient Indian texts and Islamic, Persian, and European astronomical studies, was determined to create instruments of greater accuracy than what brass tools of the time could offer.

The result? A set of massive stone and marble instruments, meticulously calibrated to track celestial movements, measure time, predict eclipses, and study the declination of planets. The Jaipur Jantar Mantar is the largest and best-preserved of the five such observatories built by the Maharaja across India—in Delhi, Ujjain, Mathura, Varanasi, and Jaipur.

Among its 19 instruments, the Samrat Yantra stands as the most iconic—a 27-meter-high sundial, capable of telling time with astonishing accuracy, down to 2 seconds. Its shadow, cast by the triangular gnomon onto the curved quadrants, marks the passage of time with the precision that rivaled even European counterparts of its age.

Other instruments, like the Jai Prakash Yantra, function as three-dimensional celestial charts, allowing observers to track the position of stars and planets with the naked eye. The Rama Yantra, with its cylindrical design and open sky view, measures altitude and azimuth, helping map the heavens above with stunning simplicity and precision.

What sets Jantar Mantar apart is not just the scientific genius it encapsulates, but the cultural audacity of its vision. In an age when astronomy and astrology were often entwined with superstition, Jai Singh’s observatory stood as a beacon of empirical inquiry and mathematical discipline. He believed in aligning statecraft with cosmic order—linking governance to the rhythm of the universe.

Jantar Mantar is also a brilliant example of Indian architectural innovation. These instruments were not merely functional—they were monumental, durable, and aesthetically integrated into the city’s design. They invite visitors not only to observe but to interact, to trace the sky with their eyes and witness time etched in stone.

Today, as we race through the digital age, Jantar Mantar serves as a timeless reminder of India’s profound dialogue with the cosmos—a place where science was not a separate discipline, but part of life, art, and philosophy.

In rediscovering Jantar Mantar, we don’t just uncover stone instruments—we uncover a civilization’s relentless quest to understand its place in the vast cosmic dance.